As I stood at the top of the staircase in the academic building at my august British university, the voices began: “Failure. Flunkie. Flop.”

I had just experienced what was, and remains, the most awkward, humiliating moment of my life. In the final hour of my seven years of effort, my two oral examiners had just rejected my PhD work. After hearing the news, I had to stand up in front of them, cram my useless 400-page paper into my briefcase, and exit the room in heavy silence. One of them had simply stared at me without expression; the other never made eye contact.

Classes were letting out, and the atrium below bustled with throngs of students, chattering and laughing. Their journey of chasing their dreams was just coming to birth, whereas mine had just died.

Carefully I descended the stairs—ashen, weak, almost too stunned to breathe—out of the building, down the path, and through the front gate, never to set foot on that campus again.

And the voices followed me: “Screwup. Moron. Misfit.”

I flew home to my dream job as a Christian high school teacher and soon learned that, for reasons I still do not know, my contract would not be renewed. So – on the last day of school there – I exited in shame from that campus too, never to return again.

And the voices continued: “Worthless. Washout. Idiot.”

Those voices would continue in my head for many years after that disastrous winter of 2008. I heard them in the quiet of solitude, whenever I was alone. I heard them in the dark while falling asleep, and again upon waking in the night. I heard them in the shower and while walking the dogs. And I heard them in waiting areas before job interviews. (Interviewer: “What would you bring to this organization?” Me: “I don’t know…a pulse?”)

I was so devastated by my losses that I figured there must be some truth to these voices. They became extremely hard to ignore.

Further, I truly believed (and still believe) that God had led me to that PhD program and that dream job, both of which began well but ended in disaster. And for a long time afterward, this belief led to even more accusations: “God tricked you; he led you into a trap. You have a right to be bitter toward the university, your advisors, your examiners, your boss, and even your God. Go ahead, curse them.” In an odd way, I am grateful that I was too numb, too paralyzed to act on those voices. But I still had to hear them.

Since that painful year, and the death of my life dreams, I continue to get questions from caring people who can’t understand why it all happened, but they try. The most frequent theory is that Satan caused me to fail because he was threatened by what I might have accomplished If I had succeeded.

Yet to me this explanation doesn’t wash, because it makes God and Satan sound almost like equals. You know, thrust and parry: God tries to advance his plans, and Satan counters to thwart them. Superhero vs. arch-villain. But this view gives too much credit to Satan, and far too little to God.

True, Scripture teaches that Satan is very real and powerful, and that he “prowls around like a roaring lion looking for someone to devour” (I Peter 5:8, NIV). But it also teaches that God alone is almighty, and Satan is simply one of God’s created beings. He can only do what God allows; he is not capable of creating obstacles or countermeasures which can successfully thwart God’s will.

In fact, Satan is not nearly powerful enough to do most of what we attribute to him. Even the trials of Job are credited not to Satan but to human attackers (vv. 14-15, 17) and freakish acts of nature (vv. 16, 18-19) – except for the trial of painful sores, with which Job is “afflicted” by Satan (Job 2:7, NIV). Still, Scripture consistently teaches that Satan’s power is limited, both in scope and in nature, and that even the limited power he does have is further limited by what God allows.

But Satan does not need to have power over circumstances to stop us. Instead, his weapon is words. Everyone takes a beanball to the head now and then, and Satan doesn’t necessarily throw the ball; he just messes with our minds after it happens. In fact, the primary power attributed to him in the Bible is the power to deceive. Jesus calls him “the father of lies” (John 8:44, NIV). His first words in Genesis are a lie: “You will not certainly die…” (Genesis 3:4, NIV).

But Satan does not need to have power over circumstances to stop us. Instead, his weapon is words. Everyone takes a beanball to the head now and then, and Satan doesn’t necessarily throw the ball; he just messes with our minds after it happens. In fact, the primary power attributed to him in the Bible is the power to deceive. Jesus calls him “the father of lies” (John 8:44, NIV). His first words in Genesis are a lie: “You will not certainly die…” (Genesis 3:4, NIV).

And when he goes out roaming around, “looking for someone to devour,” his roar is dressed as a whisper.

He whispers to a lonely spouse, “Have an affair – what’s the harm?” He whispers to a depressed elder, “Go ahead, swallow the pills; everyone will be better off.” He whispers to a bullied teen, “Kill them all – they deserve it!”

He coaxes unsuspecting people to do his dirty work for him, causing waste and destruction in our own lives and in the lives of others.

And he whispers to all of us:

“Guilty.”

“Garbage.”

“Waste of oxygen.”

Which brings me back to the words in my own head: “Stupid. Nobody. LOSER.” When I was smashed into the canvas by a series of deadly blows to the head, Satan did not deliver the blows. No, instead he was the one kneeling over me, sneering, “Stay down, you piece of trash.”

His attacks were—are—just words. Powerful, persuasive words.

For me, sometimes those words were almost persuasive enough to make me slam my car into a retaining wall on some desolate highway.

But lies are just that: lies. They are not truth. And truth is the greatest defense against them.

So if Satan’s weapon is lying, and he’s very skilled at it, how do we win against it?

As with everything else, Jesus shows us how.

After Jesus fasts and prays for forty days in the wilderness, Satan comes to him (Matthew 4:1-11) – but again, not as a peer, like a strong villain overcoming Superman with kryptonite. No, Jesus is God, and Satan can’t match him head-to-head. So, true to form, Satan fights him with lies alone.

After Jesus fasts and prays for forty days in the wilderness, Satan comes to him (Matthew 4:1-11) – but again, not as a peer, like a strong villain overcoming Superman with kryptonite. No, Jesus is God, and Satan can’t match him head-to-head. So, true to form, Satan fights him with lies alone.

And Jesus responds not with lightning bolts or heavenly armies, but simply with truth. Of course, it helps that Jesus is truth (John 14:6). But that same Jesus – the Word of truth – lives in us as we are guided, counseled, and comforted by the Holy Spirit. So we have direct access to God’s pure truth.

The key is listening through the din of lies to find that truth, which is often much quieter – like the still, small voice heard by Elijah (I Kings 19:11). And learning to hear it usually happens over time.

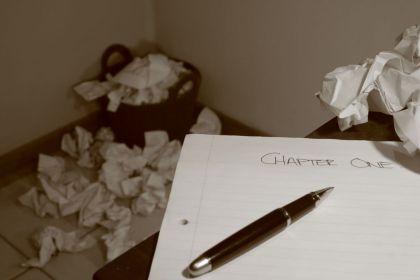

When I was nearly overcome by Satan’s deceptions, even in my numbness I had the presence of mind to surround myself with truth. While I did almost everything I could to withdraw from the world, I also joined a home community – a small group of believers who shared their own brokenness and stepped into mine. I went to church. I read scripture. And I started to write. As I typed Satan’s lies and saw them onscreen, their falseness was exposed in the light of truth.

The truth of redemption is woven throughout the entire Bible story, which shows ordinary, broken, sinful people being loved, rescued, and used by God. As I studied how gently and persistently he worked with them, I began to trust that he is constantly doing the same with me.

So, over time, I am being rescued from lies by Christ Jesus, who himself is the truth (John 14:6), the Word of God (John 1:1). This Word created me, loves me, and came not to condemn me but to save me (John 3:17).

Gradually, over a period of years, he is giving me new words. Words of truth.

I hear the words: “Failure. Flunkie. Flop.” But God’s Word says: “Failure isn’t the end; I have a future for you” (Jeremiah 29:11).

I hear the words: “Screwup. Moron. Misfit” and “Worthless. Washout. Idiot.” But God’s Word says: “My grace covers every misstep, every sin” (2 Corinthians 12:9).

I hear the words: “Guilty. Garbage. Waste of oxygen.” But God’s Word says: “I love you, and I died to forgive you and bring your life meaning” (Romans 5:8).

And finally, I hear the words: “Stupid. Nobody. LOSER.” But God’s Word says: “Precious. Beloved. Child of God!”

This truth is life-changing. And we are not meant to experience it in parsimonious sips, like wine-tasters. We’re meant to dive into it, bathe in it, gorge on it—fully baptised in it, heart and soul.

Satan’s power is the power of lies. And our weapon against him is truth.

In truth, one heals.

In truth, lies are silenced.

In truth, Satan is defeated.

I just returned from a week in Helena, Montana.

I just returned from a week in Helena, Montana. Then, more shocking events: On Bastille Day, a truck-driving terrorist in Nice, France, mowed down scores of people, injuring hundreds and killing over 80; and a college student was shot dead in the streets of Helena, Montana. The Nice attack was stunning in its unspeakable scope and depravity; the world reeled from the shock. But for me, the Helena attack was even more personal. Helena was my utopia, my retreat. And just like that, my little self-made haven crumbled into dust. I realized that even there, evil is present. Even there, tears flow and hearts cry out to God. Even there, despite my best attempts to get away from it all, none of us can escape a broken, sinful world.

Then, more shocking events: On Bastille Day, a truck-driving terrorist in Nice, France, mowed down scores of people, injuring hundreds and killing over 80; and a college student was shot dead in the streets of Helena, Montana. The Nice attack was stunning in its unspeakable scope and depravity; the world reeled from the shock. But for me, the Helena attack was even more personal. Helena was my utopia, my retreat. And just like that, my little self-made haven crumbled into dust. I realized that even there, evil is present. Even there, tears flow and hearts cry out to God. Even there, despite my best attempts to get away from it all, none of us can escape a broken, sinful world.